Disclaimer: I do not believe in Marxist socialism; I don’t have a problem with a social safety net, however.

Recently on Facebook—words which often do not bode well—a friend of a friend was not happy that his personal definition of socialism wasn’t accepted as a universal definition:

The government owns and controls the means of production; personal property is sometimes allowed, but only in the form of consumer goods.

Because his personal definition wasn’t accepted, he couldn’t create strawmen arguments to knock down, nor could he meaningfully engage in debate because, gosh, it was simply unacceptable that the definition he just Googled wasn’t good enough for the other debate participants.

Except that this definition, for what it’s worth, is the one that is largely accepted today in the US. Meanwhile, in La Rochelle, a lovely medieval town on the West coast of France (one in which I used to live), they’re expanding the harbor to provide better services to billionaire’s super-yachts. It’s socialists who voted to do so because La Rochelle is undeniably a socialist town. Turns out the socialists here in France often have no issue with private property or money, but they strongly object to the abuse of either.

For Americans, it gets even more confusing when self-described “democratic socialist” Bernie Sanders says “thank God” for capitalism.

So what gives? Do socialists agree that private property is OK or that it should be abolished? Can’t have it both ways, can you?

Summary

Because, sadly, modern people’s attention spans for reading are short, I’ll share the definition of socialism now and you can decide if you’ll continue reading or not.

Socialism: a political or economic system that promotes social welfare.

That’s it. And it’s not exclusionary. If we look at the social democracies known as the Nordic Model, they are very pro-capitalist and promote business welfare, too.

So how do we get from government controlling the means of production to this definition? That takes a bit of explaining.

History

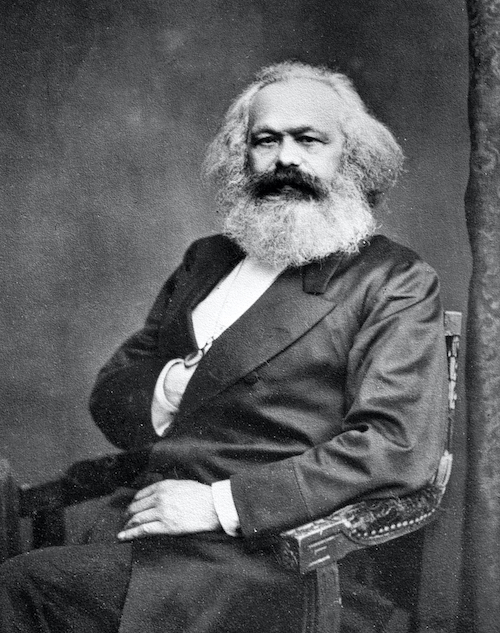

You can’t have a meaningful discussion of the meaning of socialism unless you understand the origin of the idea. And no, Karl Marx didn’t come up with it. His most famous work, Das Kapital , was published in 1867, but it was fifty years earlier, possibly with the publications of work by Robert Owen , that socialism was gaining traction. However, you can’t even appreciate this without context.

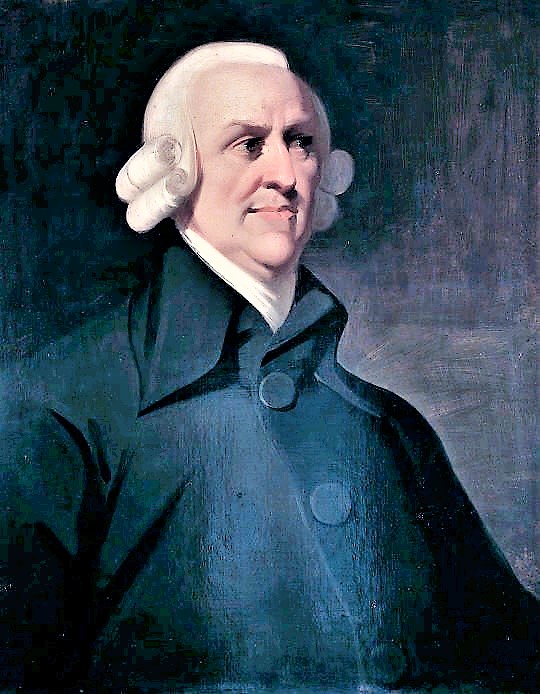

In 1776, Adam Smith published The Wealth of Nations , a book today regarded as one of the first books describing modern economics. And honestly, it had to be. The foundations of modern economics are land, labor, and capital. Historically, land wasn’t freely bought and sold. It was largely held by nobility who would no more think of selling their ancestral properties than you would think of selling your parents. The concept of laborers freely seeking the best possible wage also didn’t exist. In the middle ages, most people were serfs, tradesmen, clergy, or nobility. Fiefs, lands to which serfs were tied, still existed in the 17th century . And utilizing capital to leverage your wealth to build even more wealth wasn’t really a thing because modern economic thought was, well, not thought of. In fact, the innovative possibilities of capital combined with profit-seeking labor is very much a modern invention.

Adam Smith came along when economies were transitioning from zero-sum Mercantalism to industrialized capitalism. With the birth of the industrial revolution in the mid-1700s, we started to see a magnificent growth in profits. We also saw a magnificent growth in new forms of human misery. In the paper entitled Time and Work in 18th-Century London , Hans-Joachim Voth cites Herman Freudenberger and Gaylord Cummins as arguing that

annual labor input possibly increased from less than 3,000 to more than 4,000 hours per adult male between 1750 and 1800.

That’s up to twice the hours most Americans work today (and Americans tend to work far more hours than most other developed nations).

And frequently those laborers were children. It appears that many children were effectively slaves during the industrial revolution . And by “slaves”, I mean that with all of the horrifying implications. Robert Heilbroner, in his famous economic history The Worldly Philosophers wrote:

Indeed, a recital of the conditions that prevailed in those early days of factory labor is so horrendous that it makes a modern reader’s hair stand on end. In 1828, The Lion, a radical magazine of the times, published the incredible history of Robert Blincoe, one of eighty pauper-children sent off to a factory at Lowdham. The boys and girls—they were all about ten years old—were whipped day and night, not only for the slightest fault, but to stimulate their flagging industry. And compared with a factory at Litton where Blincoe was subsequently transferred, conditions at Lowdham were rather humane. At Litton the children scrambled with the pigs for the slops in a trough; they were kicked and punched and sexually abused.

Sadly, these accounts of the horrors of child labor during the industrial revolution are not scarce. Is it any wonder that many people objected to this new idea of capitalism?

One of the most prominent objectors was the aforementioned Robert Owen. A highly successful businessman, Owen was aghast at how workers were treated and decided to buck collective wisdom and create a more humane business. In 1799, he purchased New Lanark Mills and

Under Robert Owen’s management from 1800 to 1825, the cotton mills and village of New Lanark became a model community, in which the drive towards progress and prosperity through new technology of the Industrial Revolution was tempered by a caring and humane regime. This gained New Lanark an international reputation for the social and educational reforms Owen implemented. New Lanark had the first Infant School in the world, a creche for working mothers, free medical care, and a comprehensive education system for children, including evening classes for adults. Children under 10 were not allowed to work in the Mill.

And Heilbroner reports that from 1815 to 1825, there were over 20,000 visitors, including nobility and business owners, all trying to figure out how this mill had become hugely profitable.

Owen, along with Henri de Saint-Simon , Charles Fourier , and others, formed what we today call the “Utopian Socialists.” Generally speaking, they were a reaction to the brutality of the industrial revolution and these thinkers envisioned better worlds, or utopias, based on decency, kindness, and social needs. However, with the possible exception of Owen’s direct action in New Lanark, these were imagined worlds, built on dreams, not evidence.

They were, however, the first socialists, they were all over the map, and they had little to do with governments controlling the means of production.

In contrast to them were the Ricardian Socialists . They focused quite heavily on the labor theory of value which argues that the value of a good or service is the total amount of labor required to produce it. Yes, many people think that’s Marxist because Marx was quite fond of it, but their beloved Adam Smith championed it! In Chapter V of Wealth of Nations , he wrote:

The value of any commodity, therefore, to the person who possesses it, and who means not to use or consume it himself, but to exchange it for other commodities, is equal to the quantity of labour which it enables him to purchase or command. Labour therefore, is the real measure of the exchangeable value of all commodities.

The Ricardian’s (so-called because David Ricardo also accepted the labor theory of value and his arguments heavily influenced them) argued that because value is derived from labor, those who labor deserve the rewards. This is curious to me because it often implies that managers and owners who supervise and direct physical labor—often without doing it themselves—are somehow less valuable, but I digress.

To the Ricardians, labor should reap the rewards of commerce, but is instead exploited. One of these was Thomas Hodgskin and the opening paragraph from Wikipedia sums up many issues quite nicely (emphasis mine):

Thomas Hodgskin (12 December 1787 – 21 August 1869) was an English socialist writer on political economy, critic of capitalism and defender of free trade and early trade unions. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the term socialist included any opponent of capitalism, at the time defined as a construed political system built on privileges for the owners of capital.

For Hodgskin, capitalism was built and maintained to serve the privileged class. However, he didn’t object to capitalism per se. He objected to what we might call crony capitalism . He didn’t want a world where one prevailed due to government meddling and backdoor deals; he was, in fact, a Libertarian who loved the market system, but championed labor. He insisted on the rights of unions to exist and advocate for workers (because which Libertarian would object to free association?) and he strongly objected to rent-seeking behavior . But he was definitely a capitalist, through and through. And a socialist in that he advocated for the needs of society, not just the monied class.

Marx

It wasn’t until Karl Marx came along and skewered the Utopian and Ricardian socialists, that people started thinking of socialism in terms of Marx’s more specific view. This was, in part, because in The Communist Manifesto and other writings, Marx and Engels created a more detailed description of, and argument for, socialism. They both acknowledged the moral considerations of the Utopian and Ricardian socialists but destroyed them for being fantasies. And given that the Manifesto called for revolution and swayed many people, Marx’s views on socialism were indelibly etched in people’s minds.

In particular, in The Communist Manifesto Marx wrote of the Utopian socialists:

By degrees, they sink into the category of the reactionary [or] conservative Socialists depicted above, differing from these only by more systematic pedantry, and by their fanatical and superstitious belief in the miraculous effects of their social science.

But what of his own views? In the Manifesto, Communism is the result, but socialism is a necessary step:

We have seen above, that the first step in the revolution by the working class is to raise the proletariat to the position of ruling class to win the battle of democracy. The proletariat will use its political supremacy to wrest, by degree, all capital from the bourgeoisie, to centralise all instruments of production in the hands of the State, i.e., of the proletariat organised as the ruling class; and to increase the total productive forces as rapidly as possible.

And that is effectively the definition that many hurl against socialism today: naïve workers gutting honest, hard-working, private enterprise in favor of an inefficient nanny state. Or to phrase it in the other extreme: the proletariat rising up against the bourgeoisie to put power in the hands of the people.

Personally, I don’t buy either definition because a) I don’t see it happening and b) I can’t help but roll my eyes at those those think the definition of an ever-evolving word must be set in stone by an essay written 172 years ago, ignoring all modern thought on the subject.

Words Mean Things

Yes, words mean things and then they mean other things. For example :

Girl meant any young person – “gay girl” meant girl, not lesbian, and “knave girl” meant boy – while “man” meant any person, regardless of gender.

The word “girl” was originally gender neutral and arrived in the English language around 1300 CE , but we’re not certain of its origin.

Or consider that the word “meat”, coming from the Old English maet, simply meant “food” and its current definition of “animal flesh” didn’t arrive until the 1300s.

Words, of course, have no intrinsic meaning. When I hear the word “peer”, I think something like “equal in quality”, but if I’m speaking French, the word « pire » has the same sound as “peer” but means “worst,” a radically different meaning.

Words have the meaning we ascribe to them and nothing more. But this causes many problems if we don’t understand that another’s definition is different from our own. For example, some people think “meat” only means pork or beef, leading to ridiculous incidents of vegetarians being served chicken because they “don’t eat meat.”

So if you have a definition of socialism that doesn’t match my own and we don’t realize this, it’s very easy to have a confused argument. So what do people think socialism means today?

According to a 2018 Gallup poll of Americans :

| 2018 | 1949 | |

| Sep 4-12 | Sep 3-8 | |

| Equality - equal standing for everybody, all equal in rights, equal in distribution | 23% | 12% |

| Government ownership or control, government ownership of utilities, everything controlled by the government, state control of business | 17% | 34% |

| Benefits and services - social services free, medicine for all | 10% | 2% |

| Modified communism, communism | 6% | 6% |

| Talking to people, being social, social media, getting along with people | 6% | -- |

| Restriction of freedom - people told what to do | 3% | 1% |

| Liberal government - reform government, liberalism in politics | 2% | 1% |

| Cooperative plan | 1% | 1% |

| Derogatory opinions (non-specific) | 6% | 2% |

| Other | 8% | 7% |

| No opinion | 23% | 36% |

It’s interesting to note that “government control” has now slipped to second place between “equality” and “benefits and services.”

And then we have this lovely New Yorker article discussing how tangled the definition of socialism is in America today .

The Nordic Model

Or consider the Nordic Model . The social democracies which have adopted the Nordic model have strongly embraced globalization, capitalism, and social welfare. While they differ in varying degrees, key similarities in all of these countries include:

- a comprehensive welfare state

- large-scale investment in human capital, including child care and education

- labor market institutions that include strong labor unions and employer associations

Depending on where you want to draw the line, the countries which follow the Nordic model are Finland, Denmark, and Sweden, but many include Norway and Iceland in this group. These countries tend to have strong economies and, most importantly, five out of the seven happiest countries in the world follow the Nordic model. I don’t believe that is a coincidence.

Given the historical definitions of socialism, I think the social democracy of the Nordic Model fits quite well.

Types of Socialism

So now I think we can break socialism down a bit into a few different types. The following, of course, is by no means exhaustive and in some cases, is a touch at odds with definitions provided by economists.

Utopian Socliasts

Largely a reaction to the brutal industrial revolution capitalism, the utopians envisioned perfect societies, all radically different from one another. They’re generally considered to be naïve.

Ricardian Socialism

Also reacting to industrial revolution capitalism, the Ricardians accepted David Ricardo’s description of the labor theory of value and argued that all wealth belongs to the laborers. They tended to reject ideas such as rent or profit, but some, such as Hodgskin, were also capitalists.

Marxist Socialism

This is what most Americans mean when they say “socialist”, which is curious because it’s a dying breed in the West (though still somewhat popular here in France). In short, Marxist socialism is when the government owns the means of production of goods and services. Marx also called for the abolition of private property, but not personal property (consumer goods).

Democratic Socialism

In this model, democracy is paramount, but it’s combined with a drive towards a socialism closer to the Marxist ideal. There are no countries which currently follow this model.

This is what Bernie Sanders claims to be, but in reality he fits the social democrat model better.

Social Democracy

I like to think of this as “modern socialism”. There are several strands, but a key feature of Social Democracy is embracing capitalism while trying to contain its worst excesses, possibly via nationalization of problematic industries. Strong social safety nets are a key component of this. However, this leads us to ...

Social Market Economy

Though not a form of socialism in the classic sense, I feel that it fits the zeitgeist of feelings on socialism today.

This is what much of Europe has adopted today, including the economic powerhouse, Germany. It’s similar to Social Democracy, but tends to shy away from nationalizing industries. Social Market Economies tend to support the market, but not guide it, and have very strong social safety nets. They also strive to constantly understand the economy and adjust and adapt, rather than try to find a one-size-fits-all economic “Theory of Everything.”

Possibilities

Imagine a world where you don’t go bankrupt because you tripped and broke your leg. Imagine a world where you don’t have to choose between forgoing college or decades of crippling student debt. Imagine a world where you’re paid a living wage as a waiter—or you can get filthy rich building your own business empire. That’s socialism today.

And an overly simplistic review of the meaning’s evolution over time:

- Pro-social and sometimes pro-capitalist (Utopian and Ricardian socialists)

- Government control of production (Marx)

- Pro-social (today)

Yes, there are still people who will pedantically insist that Marx’s definition is the “one true socialism”, either because they agree with it or they wish to attack it. But his definition wasn’t the first, nor will it be the last. And while economists (and pedants) still cling to Marx, many of us are looking to the future and see the potential of caring about people as much as business.