A Brief History of an Inconvenient Treaty

Every few months, usually on social media, sometimes in earnest emails, I’m treated to an solemn declaration that the United States was founded as a Christian nation. And, inevitably, when I politely mention the Treaty of Tripoli , ratified unanimously by the U.S. Senate in 1797, signed by President John Adams, and containing the following inconvenient sentence in Article 11:

The government of the United States of America is not, in any sense, founded on the Christian religion.

... well, I’m informed that this line doesn’t count.

You see, it’s complicated. Or misunderstood. Or mistranslated.

Or the senators “didn’t realize it was there.”

Or “it wasn’t public.”

Or perhaps, one day, someone will suggest it was actually written by time-traveling French Freemasons with a grudge against George Washington.

History can be so exciting.

So let’s take a short walk through what actually happened, why the clause exists, and why every attempt to “explain it away” collapses as soon as you hold it up to the light.

Treaty of Peace and Friendship between the United States of America and the Bey and Subjects of Tripoli of Barbary.

ARTICLE 1. There is a firm and perpetual Peace and friendship between the United States of America and the Bey and subjects of Tripoli of Barbary, made by the free consent of both parties, and guaranteed by the most potent Dey & regency of Algiers.

ARTICLE 2. If any goods belonging to any nation with which either of the parties is at war shall be loaded on board of vessels belonging to the other party they shall pass free, and no attempt shall be made to take or detain them.

ARTICLE 3. If any citizens, subjects or effects belonging to either party shall be found on board a prize vessel taken from an enemy by the other party, such citizens or subjects shall be set at liberty, and the effects restored to the owners.

ARTICLE 4. Proper passports are to be given to all vessels of both parties, by which they are to be known. And, considering the distance between the two countries, eighteen months from the date of this treaty shall be allowed for procuring such passports. During this interval the other papers belonging to such vessels shall be sufficient for their protection.

ARTICLE 5 A citizen or subject of either party having bought a prize vessel condemned by the other party or by any other nation, the certificate of condemnation and bill of sale shall be a sufficient passport for such vessel for one year; this being a reasonable time for her to procure a proper passport.

ARTICLE 6 Vessels of either party putting into the ports of the other and having need of provissions or other supplies, they shall be furnished at the market price. And if any such vessel shall so put in from a disaster at sea and have occasion to repair, she shall be at liberty to land and reembark her cargo without paying any duties. But in no case shall she be compelled to land her cargo.

ARTICLE 7. Should a vessel of either party be cast on the shore of the other, all proper assistance shall be given to her and her people; no pillage shall be allowed; the property shall remain at the disposition of the owners, and the crew protected and succoured till they can be sent to their country.

ARTICLE 8. If a vessel of either party should be attacked by an enemy within gun-shot of the forts of the other she shall be defended as much as possible. If she be in port she shall not be seized or attacked when it is in the power of the other party to protect her. And when she proceeds to sea no enemy shall be allowed to pursue her from the same port within twenty four hours after her departure.

ARTICLE 9. The commerce between the United States and Tripoli,-the protection to be given to merchants, masters of vessels and seamen,- the reciprocal right of establishing consuls in each country, and the privileges, immunities and jurisdictions to be enjoyed by such consuls, are declared to be on the same footing with those of the most favoured nations respectively.

ARTICLE 10. The money and presents demanded by the Bey of Tripoli as a full and satisfactory consideration on his part and on the part of his subjects for this treaty of perpetual peace and friendship are acknowledged to have been recieved by him previous to his signing the same, according to a reciept which is hereto annexed, except such part as is promised on the part of the United States to be delivered and paid by them on the arrival of their Consul in Tripoly, of which part a note is likewise hereto annexed. And no presence of any periodical tribute or farther payment is ever to be made by either party.

ARTICLE 11. As the government of the United States of America is not in any sense founded on the Christian Religion,-as it has in itself no character of enmity against the laws, religion or tranquility of Musselmen,-and as the said States never have entered into any war or act of hostility against any Mehomitan nation, it is declared by the parties that no pretext arising from religious opinions shall ever produce an interruption of the harmony existing between the two countries.

ARTICLE 12. In case of any dispute arising from a notation of any of the articles of this treaty no appeal shall be made to arms, nor shall war be declared on any pretext whatever. But if the (consul residing at the place where the dispute shall happen shall not be able to settle the same, an amicable referrence shall be made to the mutual friend of the parties, the Dey of Algiers, the parties hereby engaging to abide by his decision. And he by virtue of his signature to this treaty engages for himself and successors to declare the justice of the case according to the true interpretation of the treaty, and to use all the means in his power to enforce the observance of the same.

Signed and sealed at Tripoli of Barbary the 3d day of Jumad in the year of the Higera 1211-corresponding with the 4th day of Novr 1796 by

- JUSSUF BASHAW MAHOMET Bey

- SOLIMAN Kaya

- MAMET Treasurer

- GALIL Genl of the Troops

- AMET Minister of Marine

- MAHOMET Coml of the city

- AMET Chamberlain

- MAMET Secretary

- ALLY-Chief of the Divan

Signed and sealed at Algiers the 4th day of Argib 1211-corresponding with the 3d day of January 1797 by

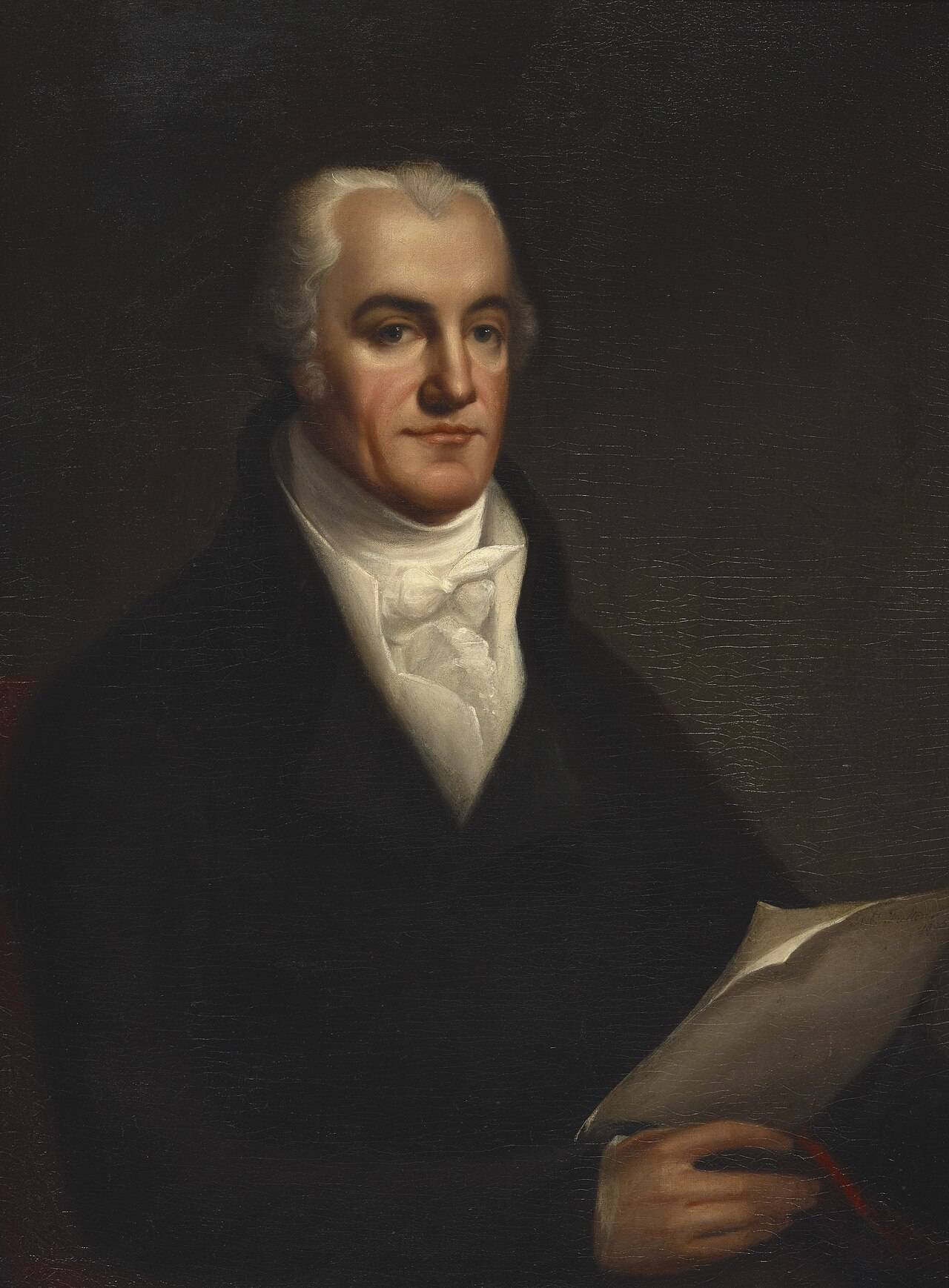

HASSAN BASHAW Dey and by the Agent plenipotentiary of the United States of America [Seal] Joel BARLOW

The Senators Who “Didn’t Notice” the Clause

The Treaty of Tripoli was ratified by the Senate of the 5th Congress:

Were they illiterate? Functionally comatose? Distracted by a 1790s version of TikTok?

No.

They read the treaty. They voted. They agreed. Unanimously.

And because this was 1797 and there wasn’t much news to print, treaties were published in newspapers, along with the Treaty of Tripoli. The newspapers included the text of Article 11 ... and nobody said anything.

Let me repeat that:

Nobody cared.

Not clerics, not politicians, not newspaper editors. The silence was deafening.

If you want to argue that the United States was understood as a “Christian nation” in 1797, you now have to explain why not one person in that era found this sentence worth complaining about.

Go ahead. I’ll wait.

“But the Arabic Version Didn’t Have That Clause!”

This argument is usually delivered with a Perry Mason-esque flourish.

Yes, the surviving Arabic text doesn’t contain Article 11, but there are three big problems with this argument.

Problem 1

Diplomatic treaties with other countries often didn’t match, word for word, across languages

Multiple versions circulated; sometimes the American draft was longer. Sometimes the Arabic version was abridged. This was normal. The Department of Foreign Affairs (a former name of the State Department ), couldn’t easily email PDFs of treaties abroad. No one flew out for negotiations for amendments. Instead, ships spent weeks sailing back and forth and late 18th century US administrative procedures weren’t exactly, um, world class.

Problem 2

The U.S. Senate ratified the English version.

The one with Article 11. The one everyone in America read. The one printed in newspapers.

Problem 3

People argue that the Arabic document we have is incomplete and ends abruptly.

And their point is ...? Damned if I can figure it out.

The Senate didn’t ratify the Arabic manuscript. They ratified the English text. They likely didn’t even know what was in the Arabic version. The attempt to wave Article 11 away by invoking missing Arabic lines is like claiming your mortgage isn’t binding because the Bank of America copy had coffee spilled on it.

So Why Did Article 11 Exist?

Because the United States was negotiating with a Muslim state, and the diplomatic custom of the time was to assure such states that America had no religious quarrel with Islam.

And who wrote that clause? Probably Joel Barlow , a poet, Enlightenment rationalist, ambassador, and also anti-slavery when anti-slavery wasn’t cool.

Barlow didn’t add Article 11 because he wanted to destroy Christianity. He added it because:

- he understood the United States government had no established religion,

- and he wanted to emphasize a simple fact: The U.S. didn’t fight holy wars.

Europe might still have been winding down its centuries-long interfaith hobby of slaughtering one another, but the new American republic prided itself on separating church from state. Hence, no religous tests allowed by the US Constitution and a pretty damned explicit First Amendment .

Barlow knew that. The Senate knew that. John Adams—no atheist—knew that. And nobody objected.

“But surely the public didn’t know about this line!”

But surely they did.

Early American newspapers were ferociously partisan and delighted to criticize the government for anything, including:

- being insufficiently Christian,

- being too Christian,

- breathing incorrectly in the direction of France or Britain,

- or, occasionally, existing at all.

If Federalists or Democratic-Republicans could have scored even a single political point by screaming, “The Adams administration just declared we’re not a Christian nation!” they would have pounced like cats on a laser pointer.

Instead? Crickets.

That is not because the press was weak. It is because nobody in 1797 thought Article 11 contradicted American identity.

The idea that the United States was founded as a Christian nation, in the modern political sense, is a much later invention.

So Why the Desperation to Explain It Away Today?

Because Article 11 is inconvenient.

It’s a clean, unambiguous sentence in a unanimously ratified treaty, signed by a Founding Father president, publicly circulated, widely printed, and uncontroversial in its own time.

It’s a historical brick wall blocking the preferred narrative, so the only option is to try tunneling under it:

- “The senators didn’t read it!”

- “It wasn’t really public!”

- “The Arabic version is different!”

- “Maybe it was mistranslated!”

- “But America was really Christian—they just didn’t know it yet!”

It’s admirable, in a way, like watching someone try to argue that “the Declaration of Independence doesn’t really say anything about independence,” because their cousin has a handwritten draft with some words crossed out.

But the historical record is what it is.

The Bottom Line

In 1797, the U.S. government had no established religion, did not understand itself as Christian in any legal or institutional sense, and said so plainly to foreign powers when appropriate. This was because, if you’ll pardon me for being blisteringly obvious, many people fled to the new world to escape having a government dictate their faith.

Only much later, long after memory had softened and myth had hardened, did Americans begin retrofitting a Christian-national identity onto the Founding Fathers, despite that being horrific to said fathers.

And when those Americans encounter Article 11?

Well... it’s difficult to build a myth on top of a document that says, “not in any sense founded on the Christian religion.”

So the mythmakers improvise. Creatively. Heroically. Sometimes even entertainingly.

But not historically.